Notes on the World and Worldbuilding

- One: Building what you want

- Two: Not building what you don't want

- Three: What is reality anyway?

- Four: Political constraints

- Five: Dreams of dreams

- Six: Dream languages

One: Building what you want

You can build anything you want. But you're not a brain free-floating in space; you're living in a society. You were taught before you could think. Your choices and biases are not entirely your own, and your work will be judged based on your context, because you are not alone. You drank up more than milk when you were young; you're a patchwork of what you believed without ever thinking about it, and what became you in reaction to the world around you.

For example, you can say, “In this world there are no gay people” or “In this world all gay people are actually evil.” These evil gays are not real people, but you and your audience are; it is perfectly okay for them to talk of your work in relation to real attitudes towards gay people, and the sorts of things people that don't like gay people let out. You can be quite blameless, but you can't be trusted to both know yourself and be honest about it.

To which you may say, “This is an outrageous invasion of my creative liberties!” But we're not talking of your freedom to imagine; for this to start you had to put your work out, for people to read it. You meant it to touch them. That means they get to talk about how it touched them, review it, critique it. And when you put it out into the world, it's going to be seen in the world. Some books get famous because they hit a vein, ring with the zeitgeist, things like that; the same way, the real world affects how imagined worlds are interpreted.

Horror fiction turns to hits when it represents something real that people are really scared by, that moment in time; the author usually doesn't notice. Tolkien became a hit because hippies liked his vision; that he didn't like hippies or their reading of his work didn't matter. We're all in this world; what we make is a sub-creation, not a separate thing.

Thrillers are grabbed from the headlines; worldbuilding is torn from your dreams, nightmares and schooldays.

Two: Not building what you don't want

You can you pass over things you don't care about. Tolkien didn't say anything about numismatics, because he didn't care, but apparently there was money in Middle-Earth. As much as people say Middle-Earth is detailed, it's skin deep on anything Mr. T thought boring or not to his tastes.

It's up to you if you must spell out the laws of nature, or make the rivers' flow make sense, or give population figures. Many did not, many would not, some could not. Most accounts that people have written about the real world don't make realistic sense either. Don't worry about multidisciplinary scientific rigor; most chroniclers didn't!

Any attempt to explain our world prior to (say) Darwin and Newton was just a mass of weak supposition and error; histories of the past twenty years don't yet have the perspective and the facts to be definitive.

You don't have to be perfect; nobody is.

Three: What is reality anyway?

Often when people talk about the world-model you made, they're really talking about the model of the real world they've got in their heads. People saying misogyny, homophobia and general dog-eat-dogness are inevitable must-haves are not always talking about the real world, but the real world model they got inside their heads. That's different from the real world model inside your head, and when people don't even agree about the real world they're not gonna agree about fantasy worlds. One person's super ultra detailed realism is another's offensive ideological woo.

We can mostly agree about realism (or not) re natural sciences, but we're so absurdly divided on social sciences. They're politicized; that doesn't necessary mean they're in dispute, but that some people want to yell about them. Every zombie apocalypse is a projection of the author's beliefs on whether only rugged individualism will carry the day, or whether people can and will work together rather than die. And it's not like enlightened centrism is the best way; with some things that's like giving women half a vote.

What this means is culture wars belong in fantasy.

That is, unless you are very milquetoast and censorious in your choice of what you make, and end up writing kid lit with blood and booba.

For example, this real world of ours: is it our one working example of a world with a God… or a world without?

Four: Political constraints

Because of these problems, there are subjects where anything you say will be read in a political way: “They meant to make a point!” You can leave that subject out, but sometimes that doesn't help.

And again, it feels like a constraint, and it is.

You can say that nothing means anything, sure; but you'd better find an audience that accepts such a proclamation first. There's a difference between telling straight jokes (or gay jokes) to your friends, or to a general audience. Your friends know how much (if anything) such jokes mean; a general audience is well justified by prior experience in assuming you're a bigot, and your apologies are just insincere damage control.

But (as the old writing saw goes), constraints are useful.

Such a constraint can force you to be not lazy, not the unexamined default or the first idea, not just the ghosts of your ancestors and the world that made you carbon-copying themselves onto the canvas of limitless possibility.

Sometimes writers are criticized because they are too far out; more often because they haven't gone anywhere. If you've heard of the Bechdel test — “a film passes the test if it contains two named women having a conversation about something else than a man” — its idea is not that it detects films that are bad. It detects a troublesome male default, since so many films do not pass it. Similarly, you should look at what you make, and ask yourself: why did I make this? Why was this the obvious choice? Who's really calling the shots here?

If you don't ask, others will.

Five: Dreams of dreams

Worlds that we make are not really that original. Pish, medieval Europe with serial numbers filed off; this author is interested in heroism, not sociology. Here's the French Revolution in space; this author is interested in the physics of things going boom, not the appalling societal regression of a far distant future.

Something that was all original could not support a story, since we'd get stuck explaining how doors work, why there are no doors, and how the very concept of spatial separation is meaningless within this physics. So we copy, and change the things we want to tweak, fade out the things we don't care for; smush things together and see what happens.

Even when we crib from others' worldbuilding, we're actually stealing from their background too: not just medieval stories, but medieval stories as a 1930s white British don of his time would make a world of them, writing between and during two propaganda-heavy World Wars.

I'm not making any claims of causation, but I think it's maybe not accidental that the way fantasy has “evil races” is a straight-out reification of how wartime propaganda talks about the Enemy. These days, those 1930s attitudes are baked in into fantasy, and usually not noticed: classic orcs; nothing to think here. But times change, and it will make some people uncomfortable reading about a world whose reality sounds like the lurid lies of a present-time far-right election pamphlet; except now the wrong skin color is green.

The worlds we make are 5% original, 10% stolen from the dreams of others, and 85% stolen from dreams of reality. Don't just gawp at the end of the pen making magic on paper; consider what's at the other end of the pen, too.

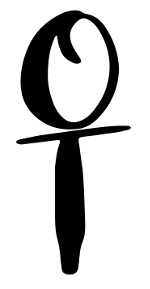

Six: Dream languages

When you build a world, you don't start from nothing. Your people are human: if not quite human, then usually bipedal with bilateral symmetry and the usual senses; if not even that, then they have human minds: hate, fear, love, curiosity, all that.

After that, the creatures and the societies you make aren't made ex nihilo either: dwarves from Tolkien, orcs from Warcraft, Forgotten Realms elves, Moomins from Tove Jansson. Knights from (vague memories of) medieval Europe, Japanese samurai with the serial numbers filed off, an ancient kingdom of paper, rockets and politeness in the east; horn-helmeted reavers across the northern seas; useful shorthands for what these people are like. (Hopefully not too much racist stereotyping, not too much leaning on “All Nyissans are treacherous drug addicts!”)

Nobody has brainspace to start with seventeen unique and nuanced nationalities: thus these are Vikings that worship bears, these are Mongols with facepaint, these are gender-flipped Romans or whatever.

The languages aren't original, either. Something is replaced with English, and after Tolkien not many have made an explicit mention of this.

The made-up languages obey your real-world intuitions of what sounds dark and evil, what solid and good, what elvish and holy, what oleaginous and tricksy: Cthol Mishrak, Valdemar, Qualinesti, Daario Naharis. Sometimes real words peek through, giving hints of what to expect: solemn Solamnia, a living pious legend king Prester John, Eomer and Eowyn for fans of Old English. Sometimes names are just names, and hopefully don't distract too much: Mica and Jon are fine, Christopher and Richard as well, Giovanni and Abdullah seem too distinctive, too laden with meaning. (Though replacing other fantasy languages with real languages, just like you pretend you replaced the most important one with English, is a practice that could work. If you're not a huge stereotyping racist, that is.)

Through all, there's an invisible filter of what is “right”: fantasy gets some mythical vagueness from how many words don't sound fantastic enough (pomeranian, Achilles' tendon, German shepherd, etc.) and must be bypassed or left out. It's cheese — not Edam or Emmerdaler — just unnamed cheese! Even when there is an explicit frame that the story is “translated” into English, some words don't ring quite right. There are “right” old-time words, but nobody wants to footnote obsolete terms for dogs, carts and pieces of armor. Thus collar instead of gorget; armguards instead of sabatons; carriages are just unspecified carriages, described but not named; vague, primal, medieval, fantastic.